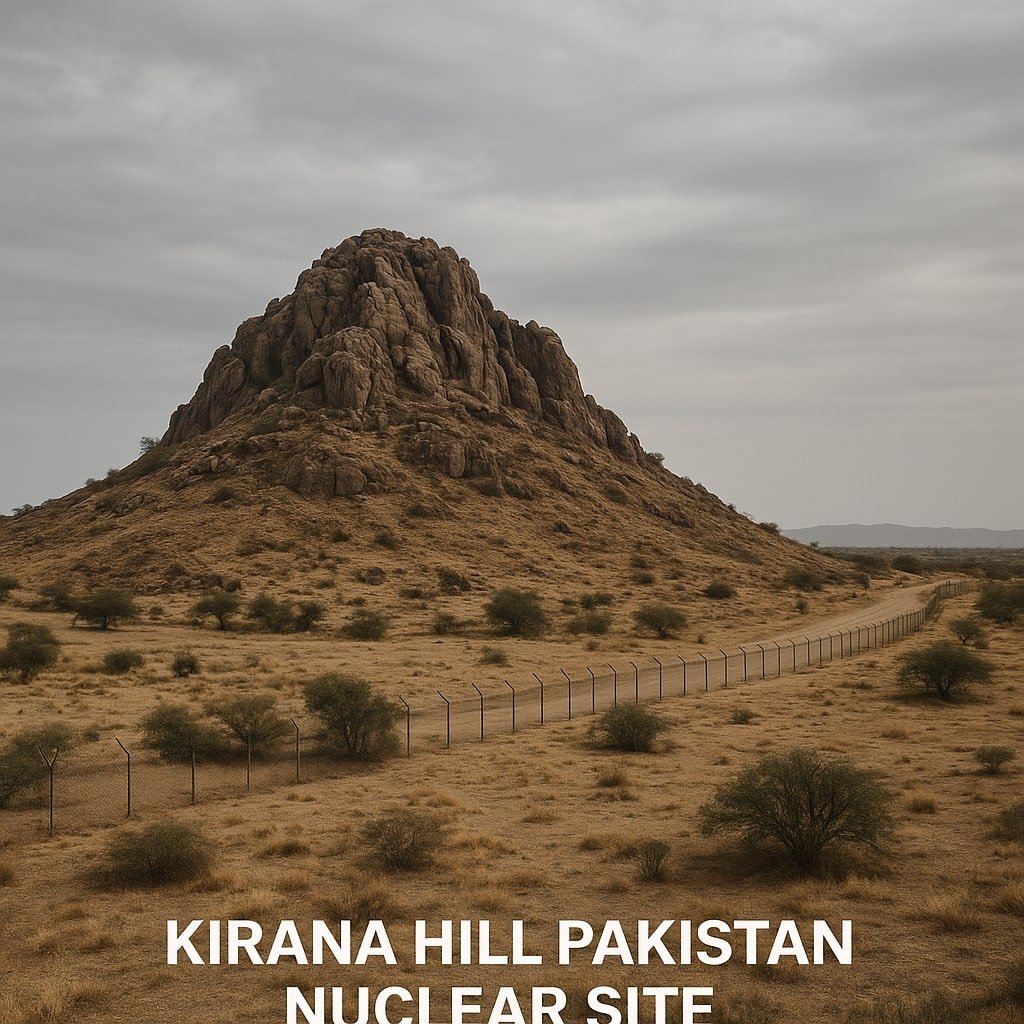

Introduction to Kirana Hill Pakistan’s Nuclear site

Located in the Sargodha District of Pakistan’s Punjab province, Kirana Hill Pakistan’s Nuclear site is a small yet historically significant range of rocky outcrops. These hills, standing isolated amidst the arid plains, might seem unremarkable at first glance. However, beneath their surface lies a story of clandestine operations, military precision, and nuclear ambition. Once an obscure geographic landmark, Kirana Hills earned a place in global nuclear history when it served as the site for Pakistan’s covert nuclear cold tests in the 1980s.

Origins of Pakistan’s Nuclear Program

Following India’s first nuclear test in 1974, Pakistan felt a growing urgency to establish its own nuclear deterrent. The geopolitical rivalry between the two nations, both emerging from the same colonial past, escalated the regional arms race. Pakistan’s leadership, especially Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, famously declared, “We will eat grass, even go hungry, but we will get one of our own.” This statement catalyzed the formation of Pakistan’s nuclear program, eventually overseen by Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan, a metallurgist with experience from Europe’s advanced uranium enrichment facilities.

Why Kirana Hills Was Chosen

Kirana Hill Pakistan’s Nuclear site offered several key advantages for nuclear experimentation:

- Geographic Isolation: Far from urban centers, the area reduced the risk of exposure or sabotage.

- Natural Shielding: The rocky terrain allowed for the construction of hidden chambers and test tunnels.

- Limited Civilian Presence: The sparse population minimized unintended leaks of information or public exposure.

In an era where global surveillance from satellites was growing, the remoteness and ruggedness of Kirana Hills became assets.

Construction and Infrastructure of Kirana Hill Pakistan’s Nuclear site

During the early 1980s Kirana Hill Pakistan’s Nuclear site, Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) and military engineers began creating an intricate network of tunnels within the hills. These tunnels, some over 100 meters deep, were built with precision to accommodate cold nuclear tests—simulations of nuclear explosions without the chain reaction. They included:

- Reinforced concrete chambers

- Electrical monitoring systems

- Cooling systems to regulate internal temperatures

The entire infrastructure was masked using camouflage netting, faux agricultural buildings, and artificial terrain to mislead aerial surveillance.

Involvement of Key Scientists for Kirana Hill Pakistan’s Nuclear site

At the heart of the Kirana Hills operation was Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan, whose uranium enrichment knowledge proved invaluable. His collaboration with PAEC scientists and military strategists ensured the site’s functionality and secrecy. The Cold Tests carried out were a collective effort involving hundreds of experts working in tight security protocols, often cut off from the outside world for weeks.

Nuclear Tests at Kirana Hill

From 1983 to 1990, over two dozen cold tests were conducted at Kirana Hills. These tests were crucial for validating weapon design and functionality without triggering a full-scale explosion. Though lacking the dramatic mushroom clouds of traditional tests, cold tests served an equally important role in Pakistan’s nuclear strategy.

These experiments:

- Validated implosion mechanisms

- Measured neutron behavior in high-pressure environments

- Simulated core behavior under detonation pressure

The Kirana experiments laid the groundwork for Pakistan’s later nuclear display at Chagai-I in 1998.

Technology and Equipment Used

Pakistan relied on a mix of imported and indigenous equipment. While some centrifuge components and scientific instruments were covertly procured from international suppliers, local engineers mastered the art of reverse engineering and innovation under constraints. The cold tests utilized:

- Implosion lenses

- Uranium dummy cores

- High-speed data acquisition systems

These experiments were run under strict laboratory-like conditions within the underground tunnels of Kirana.

Secrecy and Intelligence Evasion

Kirana’s existence as a test site remained a well-guarded secret for years. Measures taken included:

- Rotating security teams to avoid pattern detection

- Masking heat signatures using underground coolant systems

- Building fake sheep sheds and barns on test chambers

Despite high-resolution satellites from the CIA and Mossad monitoring the region, no conclusive proof surfaced until declassified reports began surfacing years later.

Impact on Local Population

While most residents of the area remained unaware of the true nature of activities, some displacement and restricted access raised questions. A few villagers were reportedly relocated, and strict military patrolling created suspicion. Rumors of strange machinery, night-time operations, and tremors became local folklore—fueling tales that live on even today.

Environmental Concerns and Fallout

Although cold tests don’t result in nuclear fallout, critics argue that long-term ecological studies were never conducted. Concerns include:

- Possible contamination from testing materials

- Altered underground water channels

- Soil degradation in the region

Independent environmental audits have been limited due to the site’s restricted access, but satellite imagery does show some land use transformation over the years.

International Reactions and Diplomacy

The US, already wary of nuclear proliferation in South Asia, raised diplomatic eyebrows once intelligence hinted at Pakistani nuclear advances. In response:

- Economic sanctions were placed intermittently

- Pressure mounted through non-proliferation treaties

- Pakistan maintained its “no first use” nuclear policy stance

Despite this, Pakistan’s consistent denial of testing at Kirana kept international condemnation at bay for years.

Post test of Kirana Hill Pakistan’s Hidden Nuclear site

After Pakistan’s successful nuclear tests in Chagai in 1998, Kirana Hills faded from headlines, but its strategic role in nuclear development was never forgotten. Today:

- The site remains under military control

- Access is highly restricted

- Its legacy is studied in defense colleges and nuclear policy programs